50mbuffalos.mono.net

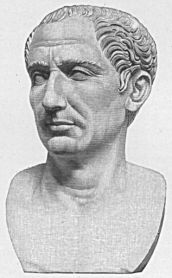

Inside the Mind of an Emperor

The fate of Julius Cesar was sealed by his greatest virtue, not his well known vices. He was ambitious; yet in his quest for personal glory he sought the glory of Rome. He strove to expand the empire, to distribute the privileges of land and ownership, and to curb the influence of the bankiers.

A learned man, equally skilled in law, mathematics, language, politics, engineering, history and architecture, Gaius Julius Cesar stood tall among his peers long before his star rose to the point by which future generations know him - as the ingenious war lord, emperor and politician, who was assasinated with 23 knife stabs.

His last will and testament granted subsidies to his murderers.

His last will and testament granted subsidies to his murderers.

Math cannot account for our conflicts

Modern history is not so modern at all. Contemporary event all follows archaic patterns rather than the principles we associate with modernity, science and secularism:

Symbolic events means more than real ones; as such 19 hijackers flying into buildings in New York, killing 3000 Americans, launched an invasion of 2 countries with combined 47.4 million citizens.

In Iraq alone approximately 100.000 civilians were killed as a consequence of the invasion due to the general state of anarchy.

Between 70.000 and 100.000 people have been subjected to the US practice of "rendition", involving kidnapping and torture in secret prison facility around the world, lost to the press, to any judicial system - and to modernity.

Symbolic events means more than real ones; as such 19 hijackers flying into buildings in New York, killing 3000 Americans, launched an invasion of 2 countries with combined 47.4 million citizens.

In Iraq alone approximately 100.000 civilians were killed as a consequence of the invasion due to the general state of anarchy.

Between 70.000 and 100.000 people have been subjected to the US practice of "rendition", involving kidnapping and torture in secret prison facility around the world, lost to the press, to any judicial system - and to modernity.

Swift strategist and eloquent speaker

Cesar was 41 and unskilled in warfare, when he became the most succesful warlord in the history of Rome.

Like Alexander, another prince benefiting from a classical education, Gaius Julius was a great orator, and like Winston Churchill he had formidable writing skills and set out to not only make history, but make sure it was read as well.

Still, scepticism abounded in his days, from Catul writing smear verses to Plutarch chastising Cesar for being less manly than the pompous and self-righteous Cato.

Also, Cesar in his early years of office would stand in the shadows of such notabilities as Gnaeus Pompeius, a widely succesful general who, even if somewhat a failure as a politician, still invoked deep devotion from Romans due to the flamboyant tales of his conquests, most notably against the Sicilian pirates.

Like Alexander, another prince benefiting from a classical education, Gaius Julius was a great orator, and like Winston Churchill he had formidable writing skills and set out to not only make history, but make sure it was read as well.

Still, scepticism abounded in his days, from Catul writing smear verses to Plutarch chastising Cesar for being less manly than the pompous and self-righteous Cato.

Also, Cesar in his early years of office would stand in the shadows of such notabilities as Gnaeus Pompeius, a widely succesful general who, even if somewhat a failure as a politician, still invoked deep devotion from Romans due to the flamboyant tales of his conquests, most notably against the Sicilian pirates.

Military conquest and economic reform

Politics today is comprised of the exact same elements as in arcane civilizations, war and economy and religion.

No matter how far you reach back into the recorded history of human civilization you will find that the same factors have made for the success or failure of a great leader of a great nation.

We are archaic beings in a hyper-modern setting.

Our technology and our scientific milestones cannot effectively hide that contemporary history is shaped by irrational instincts in the people, by petty disutes between leaders and by symbolic devotion to territorial boundaries, and by customs.

Cesar set out to change the customs of Rome, imprinting on it a multi-cultural vision, and in the end it was the threat he posed to the Roman elite that lead to his downfall in spite of the numerous services he did to Rome, his success in the battlefield and his famous magnanimous disposition, even towards enemies.

No matter how far you reach back into the recorded history of human civilization you will find that the same factors have made for the success or failure of a great leader of a great nation.

We are archaic beings in a hyper-modern setting.

Our technology and our scientific milestones cannot effectively hide that contemporary history is shaped by irrational instincts in the people, by petty disutes between leaders and by symbolic devotion to territorial boundaries, and by customs.

Cesar set out to change the customs of Rome, imprinting on it a multi-cultural vision, and in the end it was the threat he posed to the Roman elite that lead to his downfall in spite of the numerous services he did to Rome, his success in the battlefield and his famous magnanimous disposition, even towards enemies.

How Cesar built loyalty and personal legend

A legendary anecdote tells us about the peculiarly grandiose attitude of Cesar, a product of his genius, cautioning him to always try to gain the favour of anyone, and of his ambition to become a part of history, compelling him to never act out of character or do anything to spoil the image of a divine being taking heroic strides on Earth, unaffected by enmity and the pettiness of others.

As he rode through a conquered village belonging to a tribe, which had challenged him so ferociously it nearly cost him the victory, his men found Cesar's own sword hanging from a wall. They would remove it, but Cesar forbade them, saying:

"Let it hang; it is sacred."

Another time his 10th legion would defect, but Cesar responded to their sedition by offering them their freedom to leave the battle and, when it was one, share the spoil on equal terms with the men who had fought.

So ashamed by his proposition the men asked to be taken back into favour against the decimation of their ranks, a Roman military custom. Cesar refused to punish them, and he also refused to let them fight.

After fighting Brutus in a civil strife he let the captured Brutus go. Brutus immediately turned to join Pompeius who was, at this point, a rival to Cesar.

As he rode through a conquered village belonging to a tribe, which had challenged him so ferociously it nearly cost him the victory, his men found Cesar's own sword hanging from a wall. They would remove it, but Cesar forbade them, saying:

"Let it hang; it is sacred."

Another time his 10th legion would defect, but Cesar responded to their sedition by offering them their freedom to leave the battle and, when it was one, share the spoil on equal terms with the men who had fought.

So ashamed by his proposition the men asked to be taken back into favour against the decimation of their ranks, a Roman military custom. Cesar refused to punish them, and he also refused to let them fight.

After fighting Brutus in a civil strife he let the captured Brutus go. Brutus immediately turned to join Pompeius who was, at this point, a rival to Cesar.

The cost of lenience in politics

Cesar's vision for Rome was so great he knew he could not hope to accomplish it by being stern and disagreeable.

Tragically, his lenience towards his enemies also became the direct source of his downfall.

For a large part he accomplished what he set out to do, and if it had not been for Cesar, it is doubtful if Rome today would be counted among the great civilizations.

He made Rome empire.

Lesser emperors than Cesar would have cut down enemies, worried less about their historic standing and more about their personal safety.

Cesar was cut down by men he allowed to stand, hoping every time he pardoned a traitor he would be compelled to repent and join ranks with him. It was, in a sense, his lessons from the battlefield, which betrayed him.

His enormous charisma, the ability to lead men through personal vigour and bravery, his swift progress in conquest and the loyalty he invoked in men when they heard his words, mislead him to believe the same sentimental charms would work in the harsh and unforgiven game of politics.

That is the untold story the famous last words of all times:

"Et tu, Brute" (You too, Brutus?

Tragically, his lenience towards his enemies also became the direct source of his downfall.

For a large part he accomplished what he set out to do, and if it had not been for Cesar, it is doubtful if Rome today would be counted among the great civilizations.

He made Rome empire.

Lesser emperors than Cesar would have cut down enemies, worried less about their historic standing and more about their personal safety.

Cesar was cut down by men he allowed to stand, hoping every time he pardoned a traitor he would be compelled to repent and join ranks with him. It was, in a sense, his lessons from the battlefield, which betrayed him.

His enormous charisma, the ability to lead men through personal vigour and bravery, his swift progress in conquest and the loyalty he invoked in men when they heard his words, mislead him to believe the same sentimental charms would work in the harsh and unforgiven game of politics.

That is the untold story the famous last words of all times:

"Et tu, Brute" (You too, Brutus?

Julius Cesar, the first of emperors and the best. The men who betrayed him were men he had pardoned, thinking it more prudent to always try to gain the favour of men around him than to judge those who opposed him by the authority he had.